The fourth wall is a film/theatre term used to describe the imaginary barrier between the audience and the film/performance in front of them. Acknowledging the audience in any way is known as breaking the fourth wall.

Quentin Tarantino loves to break the fourth wall. But what sets him apart from his contemporaries is how subtly he does it.

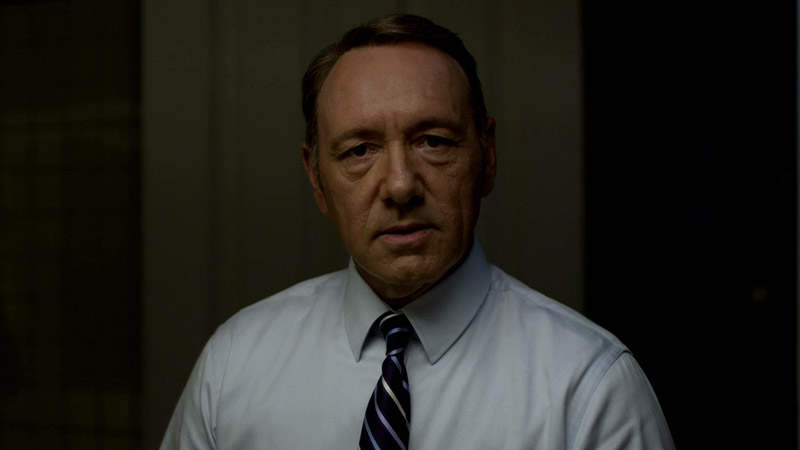

Most instances of this technique in film and television are obvious—none more so than when a character looks right at the camera and addresses the viewer. At the moment, perhaps the most popular use of this technique is done by Kevin Spacey in House of Cards (2018 editor’s note: this did not age well).

Tarantino is never so obvious. Take Pulp Fiction for example. At the beginning of the film, when Jules and Vincent arrive at a job too early, they decide to hang back for a moment. The two men walk down the hallway to have a side conversation, but although the camera pans to follow them, it remains in place. We eavesdrop on the ensuing conversation from afar.

At the conclusion, Jules tells Vincent, “Come on. Let’s get into character.” The implication is, for one minute, the movie just stopped. Our two characters took a break, had a chat, and then walked back on set.

How is this “breaking the fourth wall”? It’s subtle but simple: Tarantino drew the audience’s attention to the craft, and by doing so, if only for a moment, we were no longer wrapped up in the illusion of filmmaking.

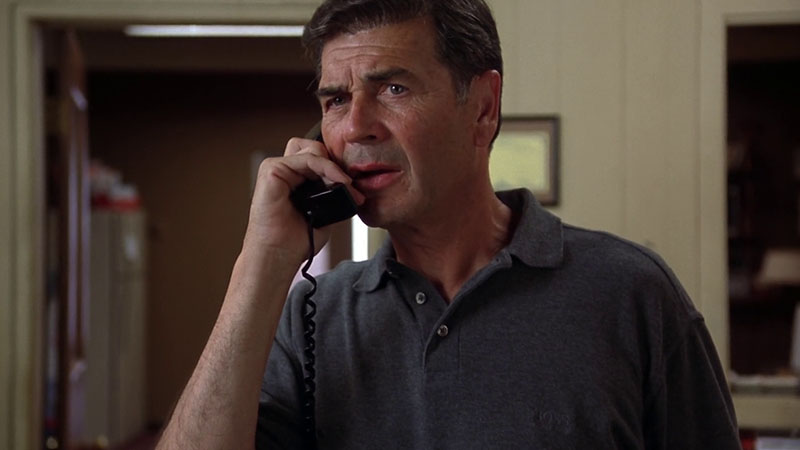

This nicely sets up my favorite “breaking the fourth wall” moment—my favorite moment in any Tarantino film—and probably one of my favorite moments in all of cinema. In the second-to-last scene in Jackie Brown, Jackie leaves Max as he fields a phone call in his office. You can see that Max has a lot on his mind and just isn’t ready at that moment to be working. He asks the person on the other line, “Could I excuse myself?” and to please call back.

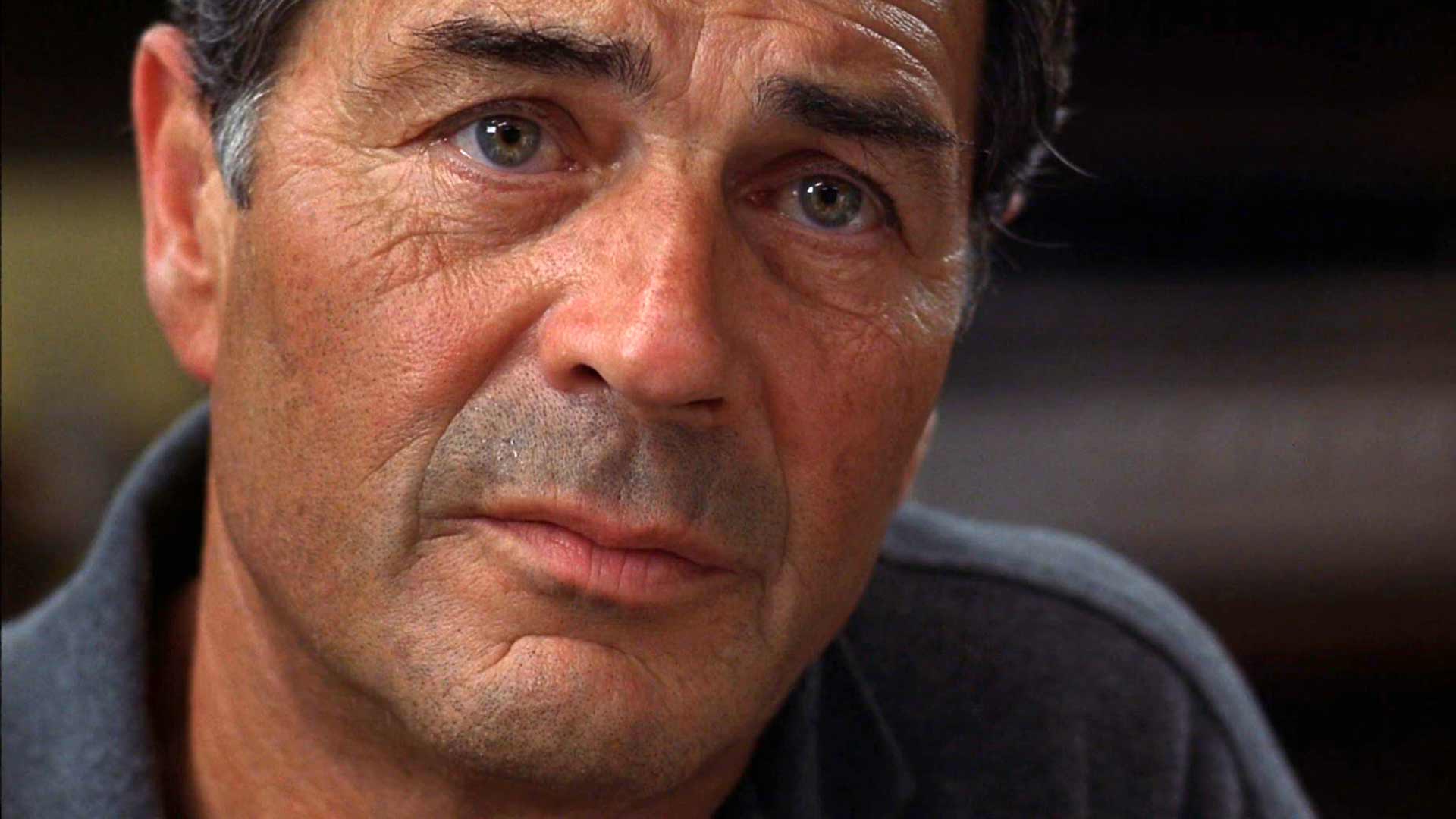

You wouldn’t pick up on this immediately—not on a first viewing—but Robert Forster, the actor playing Max, is actually addressing the audience. He’s asking the audience if he can excuse himself, not from the phone call but from the movie. This is not only his last scene in the movie—it’s his last shot.

And just like in Pulp Fiction, Tarantino opts for the stationary camera, but he does it a little different here. Robert Forster exits the scene—the movie—not stage left or stage right… he exits camera focus. The camera stays put and doesn’t rack focus to follow him as he slowly walks away, deep in thought. It’s as though the cameraman knocked off too, thinking, “If he’s done, I am too.”

This is as subtle as it gets. On a surface level Max isn’t addressing the audience at all, but rather a potential client. He’s not looking at the camera either. Only when you take in the entire context of the scene—the fact that it’s his final words in his final scene—does the deeper significance begin to shine through. Couple that with the way it was shot, and I think it was clear that Tarantino intended to draw attention to the craft. In one densely layered moment before the curtain falls, Robert Forster ceases playing Max, the character in the film, and resumes being himself. The only thing that’s missing is Tarantino yelling “cut!”.

That would be too obvious for Quentin Tarantino.