Director Ridley Scott’s 1982 science fiction masterpiece Blade Runner is not the first dystopian film ever made, but it was one of the earliest—and arguably most compelling—films to take the concept of a dystopia in a different direction.

Its forerunners largely envisaged a future that was bright, shining, and highly advanced. The dystopia didn’t breach the visual aesthetic; on the contrary, these films’ visuals were often beautiful (if sterile). Extraordinary material progress—happening at a blistering pace in the real world—was imagined to continue unabated.

But everything has to be paid for. The danger of pursuing material progress, these films propose, lay in what we might forsake along the way.

I’m thinking of films like THX 1138 (1971), Sleeper (1973), Logan’s Run (1976), the TV miniseries Brave New World (1980)—even going as far back as Metropolis (1927). I might make 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) an honorary mention: it’s almost a horror film during HAL 9000’s murderous mutiny. All of these films presented a future of advanced technology and easy living. Most of them gave us white walls and bleached white clothing, just to let us know how impeccably clean and modern the future would be.

While on the surface level these worlds appeared to be better or more advanced than our own, progress came at a devastating cost. Somewhere along the way, we sacrificed our humanity. We created a (somehow even worse) schism between the haves and have nots. We forfeited the right to grow old. We gave up love. Material progress became life’s sole endeavor, to the exclusion of everything else.

It’s at that juxtaposition—technological marvel vs. forsaking our humanity—that the sci-fi dystopia of yesteryear tantalized the imagination.

Blade Runner is also steeped in this tradition, but it foresees an entirely different endgame. In the far away future of November 2019, the Earth is an ecological disaster. The world is all grime, garbage, pollution, fire, and rain. Most animals are artificial. Off-world colonies are advertised as “a chance to begin again”.

We really fucked up here. We broke the planet. It’s beyond saving. Our best opportunity lies in leaving.

There are still technological marvels—a sprawling mega city; flying cars; artificial humans (replicants) that look exactly like us. It’s beautiful in its own hellish way. The film certainly succumbs to fetishizing its groundbreaking aesthetic at times, but I think few would come away wishing to live in this vision of a future Los Angeles. It’s hard to be wooed by it, permeated as it is—through and through—in an oppressive bleakness.

But while the visuals are fully realized, it still feels more fantasy than science—lacking in the small details that fiction requires to be believable.

If it’s raining all the time, why is it so polluted? Shouldn’t the rain clear away the smog? For that matter, why is it raining in Los Angeles so much? Have weather patterns changed so drastically?

The sun never shines. The Earth is dead. So what are people eating? When we meet the main character, Deckard, he’s ordering a bowl of noodles. Where did the rice or wheat come from to make those noodles? How can anything grow on a dead planet?

Then there’s Los Angeles. This city should be buckling under the weight of its perversions and failures, but it isn’t. Where’s the famine? Where’s the social upheaval? It doesn’t feel real because it’s still functioning seemingly well despite extensive evidence that it shouldn’t be.

That’s the larger problem: for a film that gave us arguably science fiction’s most compelling vision of ecological collapse, we don’t know what, exactly, caused it. We can guess—overpopulation and unscrupulous business practices, to name a few, but even those ring hollow. I’ve seen more people on the Tokyo subway than in the busiest scenes in this film. If we were truly exploiting the Earth beyond its limits, why is L.A. not continuing to grow? Where are the cranes and half-built skyscrapers?

Show me an empty riverbed. Show me toxic waste being dumped in the ocean. Show me anything.

It’s incomplete world building on the part of the filmmakers. The principal focus is on presenting a strong visual aesthetic, but the foundation of it is one of willful oversights. It isn’t a truthful manifestation of a world that was fully considered.

Enter 2017’s sequel, Blade Runner 2049. Unlike its predecessor, this is a film that considered everything. Moreover, it’s disciplined enough not to become mired in the little details. They exist solely as a ground upon which the world is built.

But the details are there for you to find, if you look closely enough.

The dystopia is in the details

What do people eat on a dead planet? This new Blade Runner makes that a focus right in the opening titles: a business magnate has saved the world from famine through synthetic farming. We see one such operation in the first scene. So what is it we’re eating?

Mostly insects.

It makes sense, right? We already know animals are largely extinct. Nothing green can grow without the sun, and the soil is poisoned besides. Insects are really the only source of nutrition that can survive in our broken ecosystem.

What about the rain? It’s still doing that, but the sky is also giving us snow and ash.

This is more believable than constant rain. No weather pattern continues endlessly. But what we do know about climate change is that the weather becomes more and more erratic. Rain, snow, and ash: that’s climate change on steroids. That’s what you’d expect to see on a broken planet.

Speaking of water, I appreciated K’s two-second shower, reminding us of the extreme scarcity of natural resources.

That’s later reinforced by spending time in antagonist Niander Wallace’s residence. What does the world’s wealthiest man choose for design and decor? That which is beyond the means of ordinary people, of course. On a ruined Earth, those are natural resources—wood, water, and stone. In a world in which K is told that his possession of a small, carved wooden horse makes him a wealthy man, Wallace lives amidst colossal stone walls, wood paneling, and pools of water.

Just as in the original, what we have in place of nature is a seemingly endless cityscape. Our initial approach to the Los Angeles of 2049 is very revealing, but the details are so subtle you might have missed them.

Notice something?

Where are the lights? It’s nighttime (the screenshot was brightened for detail), but the lights are all out. It isn’t until we get closer to the center of the city that we see any evidence of electricity. Either people have abandoned the outskirts of the city, or they’re living their lives in darkness.

That really leaves an impression—the possibility of these people reverting to the lives of our ancestors, huddled together in dark caves.

There’s something else, difficult to convey in a single frame: K practically owns the sky. Where’s the L.A. traffic?

That, too, makes a lot of sense. This city can’t even keep the lights on. How can the average person afford to power a flying car, if they can even buy one in the first place? They can’t. It seems almost no one can. Only policemen like K and the uber-wealthy like Wallace get the luxury of flight.

This is a city that’s failed. By presenting these failings with just enough detail to understand their causes, we’re able to believe in it.

Let’s turn to K himself, and what he represents.

K is a replicant: a bioengineered being who is indistinguishable from a human being. He has superior strength and mental capabilities, but you wouldn’t know it simply by looking at him. He appears entirely human.

Wallace Corporation can build a better one of you—beings it designs, controls, and sells like cattle. Just think about that for a minute. Imagine that such technology existed.

Does that make you feel diminished? Less important? Disposable? What does this invention do to the concept of religion, or God?

This is a recipe for social upheaval. We should see manifestations of fear. We should see acts of hate and violence.

We never got that in the original Blade Runner. At that time period, replicants were outlawed on Earth, but they would occasionally escape from their off-world servitude and try to come home. Encounters with replicants induced some fear, but also curiosity—seldom the bitterness or vitriol you’d expect.

I don’t buy it. Am I just pessimistic, or would the public positively freak the fuck out if a bioengineered being that shouldn’t have been made in the first place showed up on Earth where it doesn’t belong? I think there’d be blood in the streets. You wouldn’t be able to see the street for all the blood.

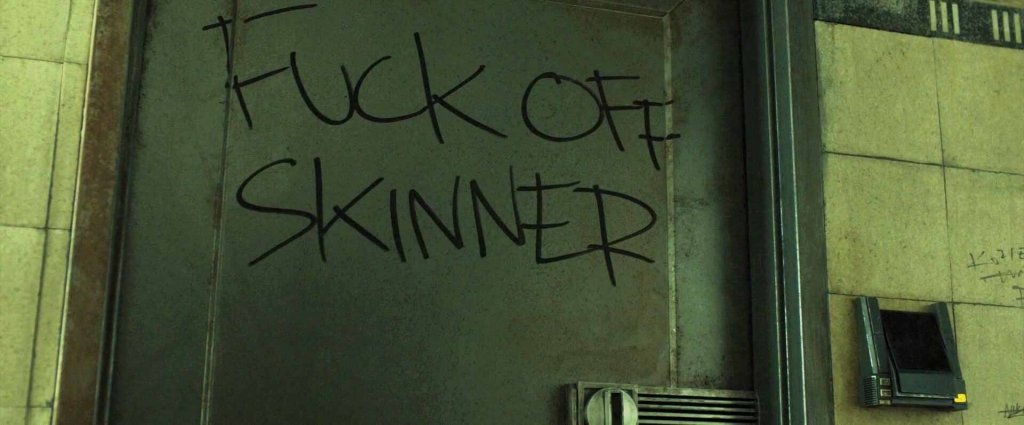

In the world of 2049, laws have changed. Replicants are allowed on Earth again. They’re designed to obey. But that doesn’t mean everyone’s okay with them.

K’s fellow officers hate him. He’s bullied, schoolyard-style, just walking through the precinct.

He’s hated at home. While the stairwells and hallways of his high rise apartment are clogged with homeless people—likely jobless or under-employed, finding anywhere they can to have a roof over their heads—K can afford an apartment. The feelings of the hallway dwellers are scrawled on his door.

If replicants were real, this is how we’d really behave toward them. These people are rightfully pissed off. They’re little better than homeless, but this artificial being has a job and a home? As opposed to manufacturing him, why not create a job for a real person?

K isn’t only a product of the Wallace Corporation: he’s a customer. He purchased his own artificially intelligent companion in the form of a software program/hologram named Joi.

For me, this is the most compelling part of the film. It’s more than just the intriguing prospect of one artificial being finding companionship in another; this plot device ties directly into the conflict.

The finite resources of a dead and abused planet mean that only so many replicants can be manufactured. What does a businessman do when no more growth is possible? In Wallace’s case, he’s managed to turn his creations into consumers. He’s bolstering his customer base with his own products.

He sells his replicants to buyers like the LAPD. Those replicants earn a paycheck, which in turn they spend on more Wallace products.

But Wallace has hit his head on even that ceiling. The only way to continue growing is if he can develop the ability for replicants to breed. His pursuit of this capability is what drives the conflict of the story.

The original film relied entirely upon its visuals to create its dystopia. The world was what it was; it lacked a clear cause. 2049 roots its world in a cause, and thus makes it real: capitalist greed destroyed the world. Wallace’s pursuit of growth and profit has sucked the Earth dry. The indelibly crafted visuals are merely the manifestation of that greed.

Doesn’t that make sense? Isn’t it believable? Isn’t it a frighteningly logical extension of the current state of our world?

This sequel didn’t change cinema like its predecessor. It didn’t show us something we’d never seen before. But Blade Runner 2049 did build a better dystopia—a smarter, fuller, and richer experience.