Tim Robinson’s very existence somehow eluded me until about a month ago.

It was Christmas 2025. My wife and I were trying to find a movie that could satisfy the both of us and my 71 year old mother. Even with virtually endless streaming choices, our viable options seemed limited. I ultimately took a chance on Andrew DeYoung’s Friendship, a 2024 film I had no familiarity with. But it had Paul Rudd on the cover image, and how can you go wrong with Paul Rudd?

I knew nothing of Tim Robinson, nor his particular brand of cringe comedy. If I’d have known, I wouldn’t have chosen this film in a million years—not for my mother. But I chose it, and we watched it. My mother didn’t finish it, but my wife and I did.

I was engrossed by it.

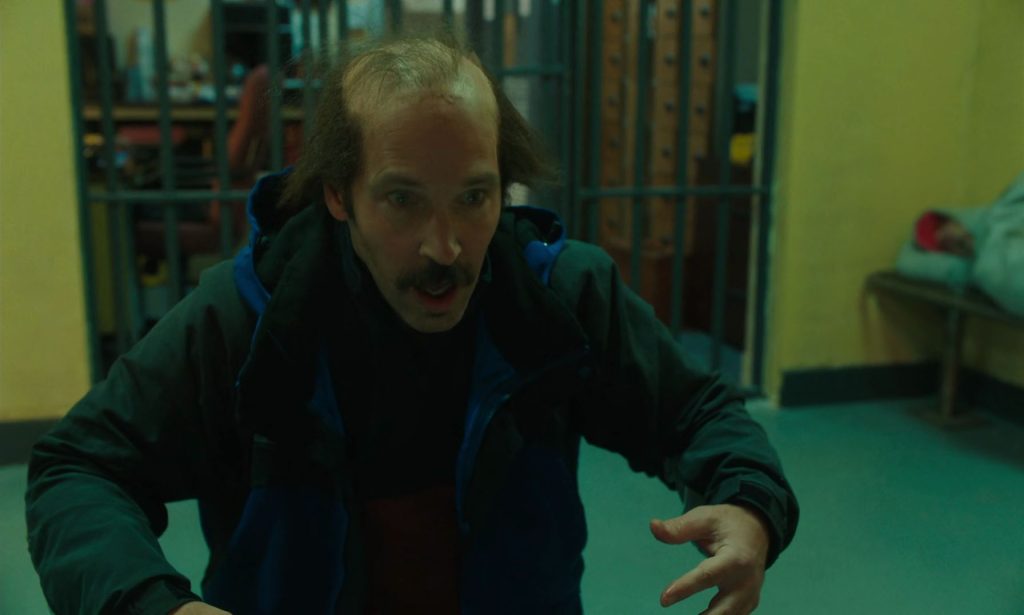

Friendship centers on Craig Waterman (Tim Robinson), a middle-aged white-collar worker struggling to connect with his cancer-survivor wife Tami (Kate Mara) and teenage son Steven, as they prepare to sell their suburban home. When charismatic weatherman Austin (Paul Rudd) moves in down the block, Craig latches onto him as a potential friend. But Craig’s desperate attempts to forge a bond spiral into increasingly erratic behavior that alienates everyone around him.

I didn’t fully comprehend it on first viewing, but I knew there were depths to be plumbed. It was only upon repeated viewings and deeper research that I realized what this film truly was.

Despite all outward appearances, I believe Friendship is not a character study of male loneliness, but rather a portrait of unprocessed grief. Craig Waterman isn’t a socially awkward husband seeking connection: he’s a widower in complete psychological denial. I contend that his wife Tami died before the film ever begins. Every scene we witness is filtered through Craig’s fractured perception of reality. The film operates as an extended unreliable narration, where Craig’s inability to confront his loss manifests as elaborate mental fabrications. The true tragedy of the film isn’t Craig’s social isolation, but his break from reality itself.

Warning: spoilers abound.

Key Plot Points

This is a more complicated film than you may believe. In considering how to proceed with an analysis, it quickly became apparent that a chronological reading of the film would not be effective. It will also be necessary to circle back to certain scenes several times, as an alternate reading of one scene forces a re-evaluation of others.

What makes Friendship so complex for me is its adherence to nearly perfect ambiguity. I’m going to present my interpretations, but they’re by no means the only correct readings of the film. Other interpretations can be made with equal authority. However, I believe that—considering all the evidence on balance—my interpretations best account for the film’s otherwise inexplicable moments.

Since there will be some amount of bouncing back and forth, it’s necessary to highlight two key plot points as a foundation to start from.

First, it’s established from the opening group therapy scene that Tami is a cancer survivor. This is a crucial plot point that should be kept front-of-mind at all times.

Second, there’s a pivotal scene at the midway point of the film where Craig takes Tami on an “adventure” to the sewer. While there, Tami goes on ahead of Craig and subsequently vanishes.

There’s so much to say about this scene, but for the moment it’s necessary to simply identify its importance to the plot. Friendship is best thought of as a film in two parts: before Tami vanishes and after Tami vanishes. There are numerous moments in the film that can only be understood in relation to this scene.

Please keep these details in mind as we move forward.

The Unreliable Narrator

To proceed, we must also define the concept of the unreliable narrator.

In literature, film, and other such arts, an unreliable narrator is a narrator who cannot be trusted, one whose credibility is compromised.

Any story told in the first person is filtered through that character’s eyes. How they perceive things is entirely subjective. If that character is affected by stress, trauma, mental illness, or otherwise, they can’t necessarily be trusted to perceive reality “accurately”—at least, what a majority consensus of “accurate” might be.

Friendship unfolds through Craig’s eyes. There’s no scene that he’s not present for. The full extent of his unreliability as a narrator is difficult to take in on one viewing, but questions should be raised for the first-time viewer via the film’s numerous fantasy sequences.

Craig imagines himself as a drummer in Austin’s band, being driven around in Austin’s dream car, and becoming a post-apocalyptic leader. In the film’s ending, Craig being arrested (in reality) is juxtaposed with his fantasy of what-could-have-been had he successfully befriended Austin’s circle. The sole function of these fantasies is to establish that Craig has an elaborate inner life.

The question we should be asking ourselves is, if he can invent scenarios such as these, what else is he inventing?

Signs of Tami’s Absence

As the film opens, the Watermans’ home is already on the market—the “for sale” sign dotting the front yard. However, there’s no clear indication as to why the house is for sale.

Knowing that Craig and Tami are parenting a 16 year old son, why would they sell their home without an extremely good reason? They’re going to uproot a teenager in the middle of high school? It’s never even stated where they’re moving to. The closest that Craig comes to speaking about it at all is when he vaguely tells Austin that he’s “about to leave the neighborhood”.

It’s very suspicious, and for me, the first clear sign that all is not what it appears to be.

But it does make sense, if you reconsider one established “fact”: perhaps Tami didn’t survive cancer. The death of a family member could absolutely be cause for selling a home. Maybe it’s too much house for Craig and Steven, or Craig can’t afford the mortgage on a single income, or there are too many painful memories associated with it.

It’s a crazy theory at first blush. After all, Tami is a presence throughout the film. She interacts directly with all the major characters. Scenes with Tami don’t play like the overt fantasy sequences noted earlier.

Considered in isolation, the house sale alone is not enough to fuel this theory. But there’s more. Much more.

There are multiple scenes of Craig arriving home to Tami loading flowers into the back of her sedan. In the first such scene, prospective homebuyers are exiting the house. They talk briefly with Craig but have their backs to Tami, as though she isn’t even there.

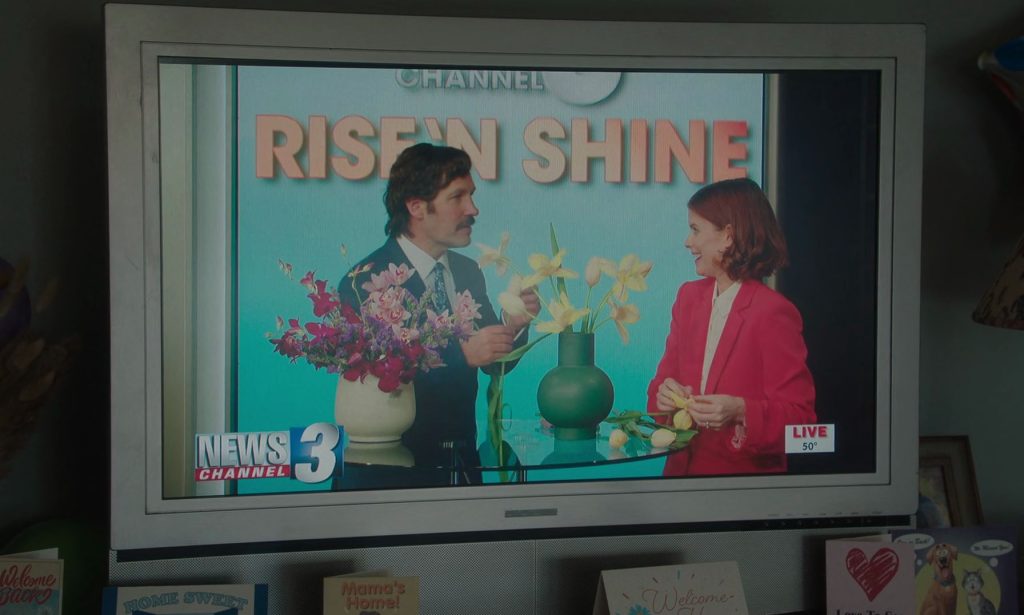

In a later scene, Craig wakes up to find that Tami is on television—with Austin—giving the weather report. That in itself is bizarre: even overlooking the fact that Tami isn’t a meteorologist, what local news station puts a random person on live TV? Steven and his girlfriend, who are in the living room with Craig, then leave—and the broadcast becomes stranger.

In the next segment, Tami is teaching Austin flower arrangement. It’s completely nonsensical, yet it’s not presented as one of Craig’s fantasies. The film is deliberately undermining its established barrier between fact and fiction. Craig is imagining this entire broadcast. Maybe he’s watching something on TV, but it’s not this.

Craig’s reality is more porous than we’re originally led to believe. Even in waking life, he’s completely fabricating parts of his experience.

Craig’s Multitudinous Fabrications

The Watermans’ son Steven has a girlfriend named Jen. She makes her first appearance at about the one hour mark, not long after Tami vanishes in the sewer. Craig jokes to Steven, “Replaced your mother already, huh?”

The timing is incredibly suspect. Tami exits, and Jen immediately replaces her as a fixture in the Waterman household? It raises questions. It begs a re-evaluation of earlier moments in the film.

There’s an early scene where Steven kisses Tami on the lips. This is not the kiss of a mother and son. Even Craig is caught off-guard by it.

In another scene, with Craig and Steven at the mall, Craig asks, “Got any crushes at school?” Steven scoffs and replies, “Of course,” as though it’s the most ridiculous question his father could have asked.

I propose a theory that brings clarity to these off-balance moments: Steven and Jen have already been together—again, before the film ever started. All the scenes in the Waterman home of the trio of Craig, Steven, and Tami were actually Craig, Steven, and Jen. Craig was imagining that his son’s girlfriend was his deceased wife for the entire first hour of the film.

Again, note the timing: it’s only when Tami vanishes in the sewer that Craig allows himself to see Jen as she really is. The mental gymnastics are simply too great: Tami can’t be missing but still a part of the household. Enter Jen, properly, for the first time.

Later in the same scene, Craig is fielding a phone call for Tami’s floral business. He breaks down in uncontrollable sobbing. One could interpret this as grief over his missing wife, but I think it makes much more sense in the context of Craig opening himself up to Tami’s death for the first time in the film.

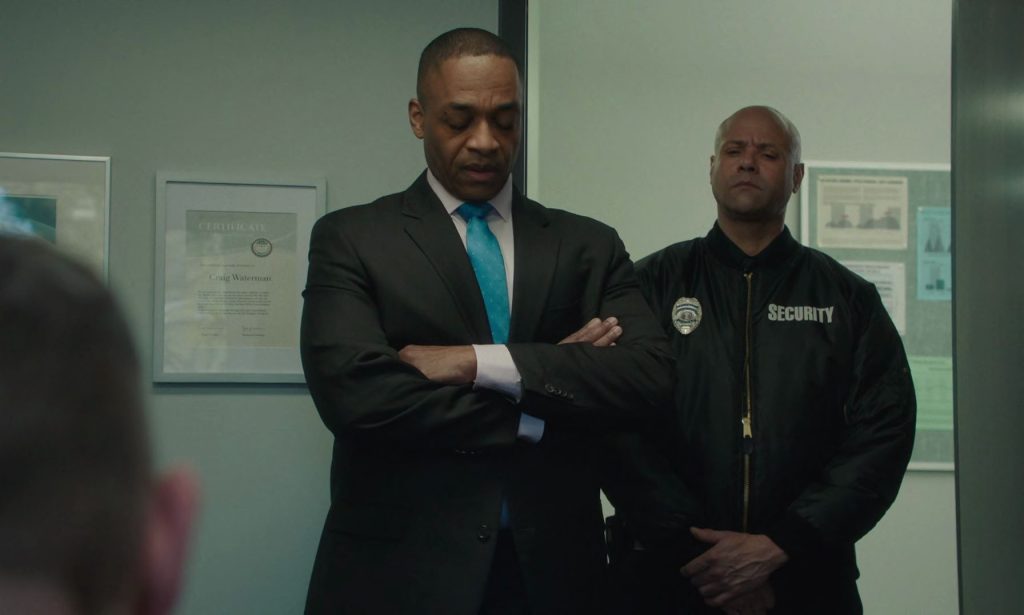

Craig is at the office in the next scene, where he torpedoes whatever’s left of his career. As his boss and a security guard stand by to escort Craig out, his office phone rings. Craig answers. It’s good news: his wife has been found.

There’s a moment here that’s incredibly revealing: when Craig goes to pick up the phone, there’s a reaction shot of his boss and the security guard. The boss looks down in exasperation and the guard furrows his brow in confusion. I believe they’re reacting to the fact that the phone never rang. From their perspective, Craig pretended—like a child—that it had. For them, it’s confusing and concerning all at once.

A Re-Evaluation of the Sewer Scene

Now that we understand the extent of Craig’s mental projections, let’s return to Tami’s disappearance in the sewer.

As we’ve established, sometimes Tami is a substitute for a real person, like Jen. Other times, such as her TV appearance, Craig is imagining her whole cloth.

In that sewer, Craig is by himself. Tami is only a memory. I believe he went there to set her free—or, more accurately, to free himself from Tami’s ghost.

In the opening group therapy scene, Tami mentioned TSDY: Try Something Different Year. “It’s like a thing we found online,” she explains. “We decided to try it out once I got better.” In the sewer, facing Tami’s reluctance to go forward, Craig references it as he upbraids her:

Christ Almighty! Can you just give this a chance? You’re always complaining that we don’t do anything new. Well, we’re here now! You’re healthy… and we’re here now! So, Jesus! Just go ahead and I’ll catch up to you in a sec.

I believe Craig is offering one last adventure to Tami’s memory in the hopes of finally letting her go. He feels guilty for all the ways he failed her in life. Perhaps he thinks that, if he can just right this one wrong, it will ease his conscious and he’ll be able to move on.

Before Tami vanishes, she gives Craig this look that’s pregnant with meaning.

Keep in mind that, in reality, Craig is only interacting with himself; Tami is Craig. That look she gives him could mean so many things. Here are a few:

- “That’s why you brought us here? You’re actually leaving me here?”

- “You think you can leave me here? Are you crazy? I am you.”

- “You honestly think this one posthumous adventure makes up for years of neglect? This is not enough to be free of me.”

In a word, she’s incredulous. This is a failed idea from the start—which, as we know, is quickly borne out. Craig couldn’t follow through with “leaving” Tami. After emotionally breaking down at home, and then going to the office and sabotaging his job, he had to backtrack. He had to re-conjure her, hence the fabricated phone call informing him that she had been “found”. Craig just isn’t strong enough to move forward without her.

The “Welcome Home” Party

All of this brings us to arguably the most surreal moment of the film: Tami’s “Welcome Home” party.

First of all: a “Welcome Home” party? An adult goes missing for a day or two, turns up again, and everybody she knows comes together for a birthday-esque gathering? The whole premise is absurd. Giving it any amount of thought makes it impossible to take at face value.

The very scene in which Tami is returned home, draped in a space blanket, she announces this party: “I’m going to get dressed. We have people coming over tomorrow.” When, exactly, did she call together a gathering of all her friends and family? On the ambulance ride home?

How, too, do we reconcile this party with the theory that Tami is deceased, and has been for some amount of time?

We’ve established that Craig is an unreliable narrator who seamlessly incorporates fantasy into his everyday reality. He fabricates his reality in part, in total, or in any degree between. If this party is a fabrication, the question is: to what extent?

If Tami is dead already—if any part of this event is to be believed—it’s something other than what it appears to be. Here’s a theory: what if it’s actually a “Celebration of Life” some months after her death? Craig has merely re-branded it as a “Welcome Home” party in his mind because he can’t face the fact that she’s gone.

This is a lot of mental fabrication. Through Craig’s eyes, Tami is actually there. Her ex-boyfriend Devin gives a speech with his arm around her. If that’s all fake, then Craig was at that gathering in maximum fantasy mode. But given all that we now know about him, it would not be out-of-character.

Before the party gets into full-swing, Craig is in his garage, sitting at the drums. One of the guests pops in, looking for the bathroom. What starts as a friendly exchange suddenly turns hostile when the guest asks, “How does it feel to ditch your wife?”

It’s hard to accidentally walk into a garage, thinking it might be the bathroom. I’m inclined to believe that Craig is alone in that garage, verbally abusing himself in another bout of Tami-related guilt. Why else would he be hiding in the garage in the first place?

The Austin Exception

Thus far, I’ve only lightly touched upon Austin, the amiable weatherman. The reason is that I believe most of Craig’s scenes with Austin really happened, which stands in stark contrast to the fabrications he weaves in almost all other facets of his life.

It would be easy to do a straight reading of this film: the struggles of male friendship in middle-aged life. Hell, it’s called “Friendship” after all. That’s a real component of this film, and I don’t want to completely discount it.

However, given this alternate reading of all the other elements of the story, a deeper look at Craig and Austin’s relationship is required.

In reality, Tami is dead. Craig is a widower. Yet, it’s Tami who tells Craig, “The mailman screwed up.” It’s Tami who tells him, “It might be nice to have a pal.” It’s like Craig was imagining that his deceased wife would have wanted him to have a friend.

This changes the Craig/Austin dynamic dramatically. Friendship is no longer a film merely about making friends: Craig seeking a friendship is born from a place of grief over his deceased wife. It’s the grieving that sits at the heart of the film. The friendship isn’t even the point; it could just as easily have been anything else to fill the Tami-sized void in his life. But once Craig latches onto the possibility of a friendship with Austin, the scarcity mentality grabs hold. He’s convinced himself it’s his only solution.

That explains Craig’s increasing desperation to forge a friendship that Austin doesn’t want. It’s not just cringe for cringe’s sake: Craig is acting as though his very survival is on the line. This is what his dead wife wanted for him. Failing her, in yet another manner, is not an option.

That, for me, is the paintbrush that colors every interaction between Craig and Austin.

This is what I believe really happened—in objective reality, not just Craig’s mind:

- Craig and Austin really met.

- They really broke into City Hall together through a secret sewer entrance.

- Craig did hang out with Austin’s larger friend group.

- Craig made enemies with all of them by sucker-punching Austin.

- Craig barged in on Austin’s workplace.

- Austin tried to politely end things with Craig.

- Craig broke into Austin’s house and stole his gun.

- Craig broke into Austin’s house again, brandished that gun, and got himself arrested.

Where I think there’s still some element of fantasy to this storyline is the earlier arrest of both Craig and Austin. It’s possible that was real, but it’s also possible it was a complete fabrication. What, in my mind, is definitely a fantasy is Craig discovering that Austin is secretly wearing a hairpiece. That reads to me like Craig inventing a shared secret to create a bond between them that was never there.

The Complete Picture

That was a lot to unpack. Kudos on making it this far.

At the beginning, I explained that Friendship is very ambiguous, but that all of these individual re-interpretations of key moments—taken together—paint for me the most complete picture.

Putting it all together, then, this is how the story actually plays:

Craig’s wife Tami got cancer. She didn’t survive. In the aftermath, Craig suffered a complete break from reality. He fabricated a fantasy in which she never died at all.

Mired in this lie, Craig is unable to help his son Steven navigate the loss of his mother. Steven copes with the situation by getting a girlfriend and having her at the house constantly. Craig incorporates his son’s girlfriend into his fantasy narrative, imagining that she’s his wife.

Perhaps owing to Craig’s unstable mental state, at some point the decision is made to sell their house.

All of the aforementioned happened before the film even started.

During the film itself, Craig’s imaginary wife pushes him to make friends with the neighbor. That went well enough for a short time, before Craig ruins it. Shunned by Austin, Craig becomes a stalker, showing up at Austin’s work, breaking into his home, and finally, threatening violence.

Craig makes no progress with his son; they both struggle with Tami’s death alone.

Craig makes one actual attempt to stop imagining his wife is alive by creating another fabrication where she vanishes in a sewer. That experiment ends in failure. He’s incapable of escaping the fantasy that he’s created.

Wracked by guilt over the ways he failed Tami in life, Craig makes vain gestures of atonement to her ghost. His final gesture is buying her a van for her floral business, which she repeatedly asked for while she was alive. Of course, since Tami’s dead, he really bought it for himself.

In the end, Craig loses everything: his wife, his relationship with his son, his job, and very likely his freedom. He’s certain to face jail time for pointing a gun at Austin and his friends.

Ultimately, Friendship is a story of utter failure—failure of its main character to come to terms with his wife’s death. All his attempts to do so are ill-conceived from the start. He’s too inept to navigate the situation. He becomes inextricably absorbed by toxic fantasies of his own creation. Everyone he comes into contact with becomes collateral damage to his crazed behavior. As opposed to getting the help he needs, he’ll likely be imprisoned and grow worse.

This is heavy, heavy stuff. And yet, it’s all hiding under the surface of a film that presents itself as a comedy—and genuinely delivers big laughs throughout.

That’s the remarkable achievement here. Writer/director Andrew DeYoung has crafted something that operates on two entirely different frequencies simultaneously: a cringe comedy that earns its uncomfortable humor, and a devastating portrait of a man’s complete psychological collapse. Grief, delusion, and self-destruction aren’t inherently funny subjects, yet DeYoung somehow makes them work as comedy without cheapening the dramatic weight underneath. It’s a high-wire act that could have failed spectacularly, but instead produces something rare: a film with real substance that’s also genuinely entertaining.

Friendship is a stunning piece of work, and my utmost admiration goes to Andrew DeYoung for pulling it off.