The digital revolution in filmmaking and film exhibition was swift and (virtually) total. The process began in earnest in the early 2000’s. In a short 10 – 15 years, it was already over. An industry inseparable from film stock for 100 years had shifted to a new digital medium.

For a change that seismic, it’s remarkable that it’s passing into history so quickly. To even call it “history” sounds slightly ridiculous: it wasn’t that long ago.

For film enthusiasts such as myself, film stock holds a place dear in our hearts. Back when film was still projected in movie theaters, I would sit a lot closer to the screen. I wanted to see the film grain. I felt in commune with the picture. It stirred something in me that digital images do not.

Let’s remember film stock. Let’s remember when and why it fell to its current diminished state. But more importantly, let’s look at what it’s becoming in this new digital age.

Film is not dead yet.

The Beginning of Digital Projection

My first exposure to the digital future that Hollywood was moving toward was my senior year in high school. I played hooky for the first and only time. My friends and I drove 100 miles to the AMC Empire in Midtown Manhattan for a very special film screening.

The date was Friday, March 30, 2001. I know this because every attendee received a souvenir, which I still proudly have.

We saw Akira, the 1988 anime film. It was billed as the “digital cinema world premiere”. It wasn’t projected on 35mm film, which was the standard at the time: it was projected digitally.

Being from 1988, this movie was originally produced on film stock. However:

- It was digitally scanned in high definition

- It underwent a digital restoration

- Without any film intermediary, the files themselves were projected digitally

The entire pipeline (save the source) was digital. This was one of the earliest commercial digital screenings in the world.

I wouldn’t have to wait long to see my next one.

George Lucas produced Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones entirely digitally. It was shot digitally, underwent all post-production using digital tools, and finally—in very select theaters—was projected digitally. I made another pilgrimage to the AMC Empire for a (midnight) digital screening on its May 16, 2002 release date.

Lucas had wanted to produce Episode I (released in 1999) digitally as well, but the technology wasn’t quite ready at that time. Three short years later, it was.

For someone who values film stock as a medium, I was strangely drawn to digital projection. It was more than mere novelty: I appreciated the cleanliness of the presentation.

Every time film is run through a projector, it experiences varying degrees of wear and tear. I remember watching Episode I several times in the summer of 1999—when it debuted, and again months later. The first time, the projection was pristine. But later in the summer, after that particular print had run through the projector probably 100+ times, it was worn ragged. This wasn’t run-of-the-mill wear: it looked like a garbage disposal tried to eat it. I remember being annoyed at how degraded the presentation was.

That never happens with digital projection. A movie is just as beautiful on the last showing as it was on the first.

At that time, being a projectionist was not the reputable occupation of skilled professionals that (I assume?) it once was. Even as a teenager, I would report projection issues to theater staff. Often, there were aspect ratio issues—the image appearing stretched too far horizontally or vertically. I can still remember the feeling of sitting in a theater, seeing a blatant issue, and wondering who could possibly be up there in the projection booth thinking, “this is okay.” This is not okay.

Even more perplexing: no one else in the theater would make a move for the door. No one would say something if I didn’t.

Fine. I’ll get up.

I remember seeing Gladiator for the seventh and final time at a second-run movie theater in 2000. Tickets cost $2. Multiple times throughout the movie, the screening abruptly stopped due to unexplained “technical issues”. That theater closed within the year, never to return.

Perhaps what I was really feeling about digital projection was malice—malice towards every projectionist who ever did me wrong. Film projection is too hard for you? Okay: you’re out of a job. You’ve been replaced by a button pusher. Calibrate the digital projector once and you’re good to go for many screenings.

The Stages of Filmmaking

But here I am, rambling on about personal stories when I haven’t laid a proper foundation.

I’ve thus far focused on only the final stage in the filmmaking process: movie exhibition, i.e. the theater-going experience. There are other stages, and any of them can utilize either digital tools or film stock:

- Production

- Post-production

- Distribution / exhibition

It’s not all one or the other: there can be a mix of both techniques across these stages. For example, Akira was originally produced on film stock but exhibited digitally in 2001. Early Pixar films, such as Toy Story and A Bug’s Life, were produced digitally but exhibited on 35mm film.

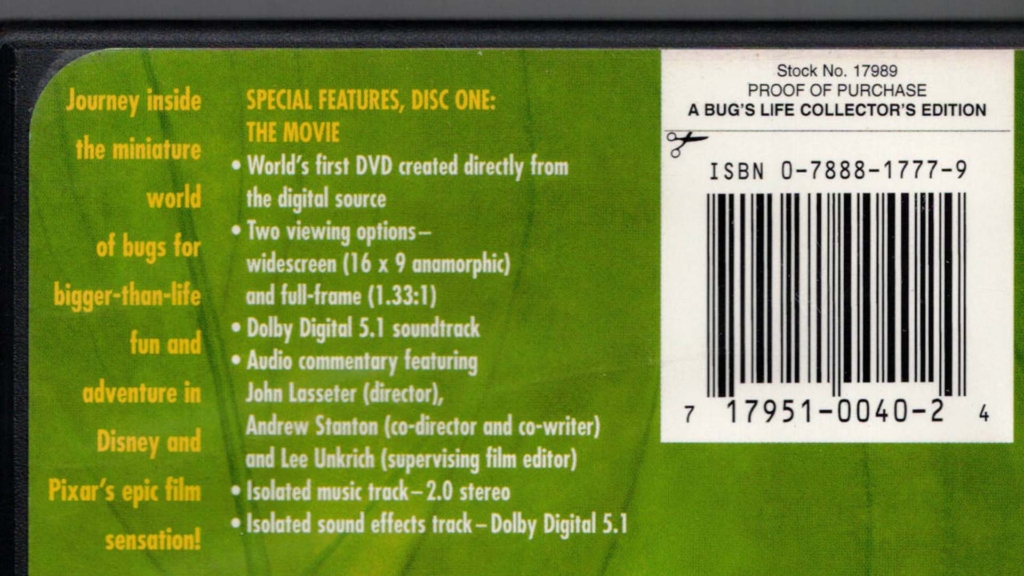

A Bug’s Life occupies an interesting place in digital history: the Collector’s Edition DVD, released on November 23, 1999, was the “world’s first DVD created directly from the digital source”. I’m quoting the DVD box art.

What does that mean? A Bug’s Life was a 3D animated movie created on computer. Production and post-production were entirely digital. The source consists of digital files. Instead of the usual process of digitizing film stock (referred to professionally as telecine) Pixar skipped the film stock entirely and converted their source files to DVD-compatible audio and video files. From start to finish—from production to eyeballs—here was a major Hollywood movie that never touched film or analog media.

This was a big deal for the digital revolution, though it went relatively unnoticed.

Bear in mind that this was a pioneering example of home video digital distribution, not theatrical exhibition. DVD had been around since 1997, years earlier than the introduction of commercial digital projectors needed for theatrical exhibition. But this was a remarkable milestone all the same.

In 2002, George Lucas provided Hollywood the blueprint of a digital future with Star Wars Episode II. In the following 10 – 15 years, filmmaking would adopt those digital workflows more and more. But in this in-between phase, movie production often utilized a mix of film and digital tools.

While high definition digital cameras were still in their infancy, many filmmakers chose to continue shooting on film stock during production. The film was then scanned in post-production to a digital intermediate (DI) where editing, color correction, and visual FX were performed using digital tools. Finally, it was printed back to 35mm film with a film recorder and distributed to theaters.

Film → digital → film.

It sounds illogical in hindsight, but that’s what made the most sense for much of the 2000’s. Digital tools simply weren’t quite good enough to completely supplant traditional film processes.

The 2000 Coen brothers’ film O Brother Where Art Thou? was the first film to utilize a digital intermediate from beginning to end. Only five years later, 50% of all Hollywood movies were using DI’s. Before the end of the decade, it was the norm.

In the mid to late 2000’s, post-production was thus the first stage of filmmaking to truly embrace digital tools.

The production stage proved trickier. It took longer for digital cameras to develop to the point of rivaling film cameras. Many filmmakers wouldn’t touch digital cameras. Some filmmakers approached them from an experimental lens (sorry), to varying degrees of success. I’ll give you a few examples from four filmmakers: Steven Soderbergh, Richard Linklater, Michael Mann, and Nicolas Winding Refn.

Soderbergh loves to experiment. Long before he shot a film on an iPhone 7 Plus, he shot 2002’s Full Frontal largely on a Canon XL1S. That’s a standard definition MiniDV camcorder—not the kind of camera most serious filmmakers would use on a Hollywood production. But Soderbergh didn’t have Star Wars money, and even if he did, I think the digital camcorder experiment would have been too enticing for him to pass up.

Do yourself a favor and skip this one: it was an astounding failure on more than just technical grounds. For a much better DV experiment, try 2001’s Tape from director Richard Linklater. It was shot on a Sony DSR-PD100A. It’s a claustrophobic movie set entirely in a hotel room. Linklater doesn’t repeat any camera positions from shot to shot—something that would have been extremely difficult to do with a bulky 35mm camera on a small set.

A few years later, Michael Mann gave us 2004’s Collateral. He used the same Sony HDW-F900 digital camera that Lucas used on Episode II. The story takes place almost entirely at night. Even with full exposure on high-speed film stock, film cameras have a limit in terms of achieving stable images in low-light situations. Digital cameras provided Mann new opportunities for nighttime shooting while using as much available light as possible.

Collateral is a unique visual experience. You wouldn’t mistake it for having been shot on film. Digital cameras still had a long way to go in 2004. To his credit, Mann embraced this camera’s limitations and made them a purposeful part of the movie’s aesthetic.

For a great deal of technical detail, read the August 2004 American Cinematographer.

Finally, let’s jump forward seven years to the high-water mark of Nicolas Winding Refn’s filmography: 2011’s Drive. It was shot largely on an Arri Alexa digital camera, which debuted only the year prior. I didn’t know this when I watched it in the movie theater during its release. I was dumbfounded when I read about it after the fact. I was used to being able to identify a digitally-shot movie very quickly up until then. Drive hoodwinked me.

Similar to Collateral, many scenes take place in the Los Angeles night. But it doesn’t share the same unique digital aesthetic. Drive looks like it was shot on film.

I knew then that digital cameras had truly arrived.

The Arri Alexa’s numerous different models would go on to become the industry standard. It’s used on a majority of Hollywood movies today.

In the 2010’s, production had shifted to the new digital world.

Concurrently, movie exhibition transitioned from 35mm film to digital projection at a rapid pace. The 2009 release of James Cameron’s Avatar—to this day the highest grossing movie at the worldwide box office—convinced many theaters to start switching to digital projectors. Only four years later, in 2013, 92% of movie theaters in the U.S. had converted to digital.

The last 35mm film projection for a new release that I ever saw was the same year—Derek Cianfrance’s The Place Beyond the Pines. I watched it at a local movie theater in Rhinebeck, New York. It was the final release that theater would project on film. Going forward, they were a fully digital establishment.

The third and final domino fell. All stages of filmmaking overwhelmingly embraced digital.

Those Who’ve Held On

If you’ve gone to a movie theater in the past 10ish years, you’ve probably seen exclusively squeaky-clean images that were shot, edited, and projected digitally. Film grain, nicks, scratches, and projection mishaps are a thing of the past.

Film stock hasn’t vanished entirely, however. Some filmmakers still shoot film and show no interest in doing otherwise.

Director Christopher Nolan is perhaps the most outspoken ambassador of film, and he leads by example. He is most invested in the last bastion of film superiority: large-format film stocks like IMAX. This is not to be confused with digital IMAX formats, which don’t come close to matching IMAX film’s resolution.

Nolan has been shooting IMAX film since 2008’s The Dark Knight, including the 2024 Best Picture winner Oppenheimer. Very few of the total IMAX screens in the United States are capable of projecting film, but some still do. If you live within driving distance of an IMAX film location, it’s well worth the experience to watch a Christopher Nolan film on the format it was shot on.

I wish I could link you to an official list of IMAX film theaters provided by IMAX themselves, but no such list is kept. I assume it’s bad for their brand to advertise which screens are inferior to others. This unofficial list from the defunct LF Examiner is as good as it gets. It was last updated in 2021.

Paul Thomas Anderson is more of a traditionalist. He doesn’t go in for new-fangled formats like IMAX. Regular 65mm was good enough for David Lean and William Wyler, and it’s good enough for PTA. He shot 85% of 2012’s The Master on the format. 65mm film negative is projected on 70mm film positive, so if you see either number, consider them interchangeable.

I saw The Master projected on 70mm at the Village East theater in Manhattan. It was magnificent. I returned nine years later to watch a 70mm presentation of another PTA film, 2021’s Licorice Pizza.

If there’s a 70mm release to be played, the Village East is probably playing it. I also made the trip in 2018 to watch 2001: A Space Odyssey on 70mm—not my first time watching this film in its original format.

Everyone knows of Quentin Tarantino. He’s many things, but “new” isn’t one of them. He draws his inspiration from the movies of the past, and the movies of the past were all shot on film. He does likewise.

2015’s The Hateful Eight was shot entirely on 65mm film. Tarantino had enough clout to get it projected on 70mm on 100 screens across the United States—an extraordinary feat in the twilight years of large format film projection. For comparison, The Master was released on 70mm on only 16 screens three years prior.

The distributor, The Weinstein Company (yes, that Weinstein), had to scavenge for enough 70mm projectors. Some of them had been out of commission since the 1950’s and needed to be repaired. Besides equipment, they had to find projectionists to operate them. It’s not like a lot of them were waiting around for their former careers to return.

I went to one of those 100 theaters. It was a visually glorious experience, even if the movie didn’t rise to Tarantino’s usual level. I’ll remember it most for a projection mishap halfway through. The film got stuck in the projector and burned a hole right through the film cell before the projectionist turned it off. If you’ve never seen this effect, it’s quite mesmerizing.

I don’t know if it was the fault of a shoddy re-commissioned projector, an inexperienced projectionist, or both. I honestly thought it was part of the movie until the projector went off and the lights went up. It seemed like just the thing a film geek like Tarantino would work into his movie with a wink and a nod. It was fun all the same.

Everything Comes Back Around

Most filmmakers—by choice or budgetary limitations—are shooting digital. Those highlighted above are the exception. They’re also some of the biggest names in Hollywood—well-established before digital became the new norm.

What happens when they’re gone? Perhaps some newer filmmakers will pick up the torch, but it’s hard to imagine their numbers doing anything other than dwindle.

However, it’s not only filmmakers who have a part to play. Only a decade or so into the digital era, the rough aesthetic of film stock is being revived among a niche group of enthusiasts—ironically, presented in digital form.

But first, let’s describe what this group is rebelling against.

When Hollywood releases their older movies on DVD, Blu-ray, or streaming, they start by digitally scanning the most original film elements that remain in their possession. If they still have the film negative, they’ll probably use the film negative. If they only have a first generation positive, they’ll use that.

Once scanned, a certain amount of digital cleanup is performed, depending on how much the studios want to spend. Much of the cleanup is innocent enough and for the better. They’ll digitally remove hairs and other debris that are an inevitable result of running film through a telecine. They might digitally stabilize an image that’s warped or otherwise shifting in the gate. Then they might apply more aggressive and controversial image processing, such as Digital Noise Reduction (DNR).

Digital releases are already cleaner looking than these movies were in their original theatrical releases. Those prints were third generation, adding more film grain and defects at each step. At home, however, we’re often seeing scans of the original camera negatives. On top of that, techniques like DNR remove even more of the film grain, resulting in immaculately smooth images.

I won’t fully condemn the effort. Frankly, it’s a miracle watching old films like The Wizard of Oz, Casablanca, and The Godfather shine like new.

But something is lost in the process. The magic of analog media such as film is just that—magic. It’s hard to put into words. There’s an impenetrable mystery embedded in those organic images. Trying to scrub it clean using digital tools scrubs some of the magic out too.

That’s what this group of enthusiasts is fighting against: the sterilization of the film medium. They don’t want clean. They want grungy and dirty, with grain the size of golf balls (okay, I exaggerate). But they want film to look like film—warts and all. In short, they want the experience of seeing their favorite films the way they remember seeing them in movie theaters years ago.

Their response? High-definition digital scans of old film prints.

Some people collect film prints. That’s a complicated and expensive hobby that many people couldn’t, or wouldn’t want to, take up. But every now and then, some obsessive, benevolent soul goes through the time and expense to scan their beat-up film print and share it with the world.

I learned about this from a good friend of mine who recently shared a download link to a digital scan of a collector’s 35mm print of the original 1993 Jurassic Park. He added the note, “has to be seen to be believed”.

He wasn’t kidding.

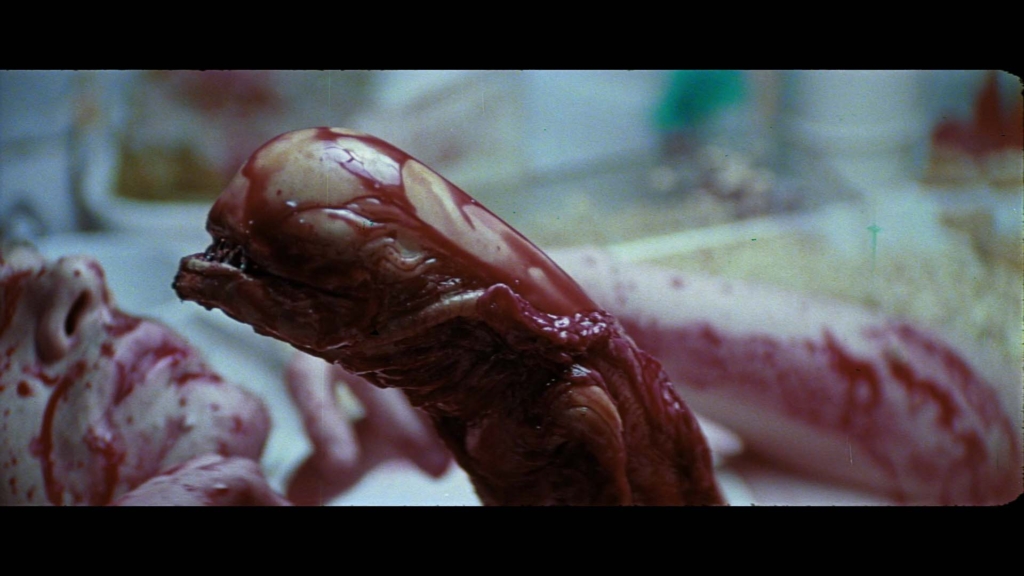

I can’t possibly describe to you the difference between this 35mm film scan and the official Blu-ray release from the studio. Instead, let me show you. Ignore the different aspect ratio and the obvious boom mics at the top of the frame. Just compare the image quality.

Now that you (hopefully) see the difference, here’s another clip of just the 35mm film scan.

To me, this is alive in a way that digital images are not.

I understand the irony: these are digital videos on YouTube. But they’re an accurate reflection of what this particular 35mm film print looks like when it’s run through a projector. Since I’m not going to collect 35mm film, this is the next best thing.

After Jurassic Park, I went searching for more. I found The Matrix, The Shining, Alien, The Silence of the Lambs, an Italian print of Manhunter, and multiple versions of the original Star Wars trilogy.

I won’t offer any links to help you locate these, but they’re out there to be found. It’s a legally fraught endeavor. Certainly no one other than the rights holders (the movie studios) can profit from these films. I would argue that these are fan edits, even though no actual content changes are being made. As long as legal versions of these movies have been purchased by all involved, and no money is being made off of their derivatives, Johnny Law typically isn’t involved.

As I said before, this is a niche thing. But it gives me heart: there are other people out there who—just like me—love film stock and don’t want to see it erased from cinema. Hopefully more and more people will scan their private collection of film prints and find a way to distribute them.

Or even better: maybe the studios can release multiple versions of their movies on Blu-ray or streaming. Offer the squeaky-clean version and a beat-up 35mm one. The cost to them is trivial. I’m talking about running film through a telecine, bouncing an encode, and doing literally nothing else.

But there has to be a financial incentive to do so. The studios need customers willing to spend money on it. My fear is that, with their current practices, they’re cultivating an audience that’s becoming completely unfamiliar with what film looks like. People don’t know what they’ve lost.

For all those who care—filmmakers and fans alike—let’s carry the torch of film as long as we can. Shoot it. Edit it. Project it if you can. Present it in any medium, even a digital one.

Let’s make sure people don’t forget how spellbinding unadulterated film stock can be.